October 2019 • News Note 61 •

October 2019 • News Note 61 •

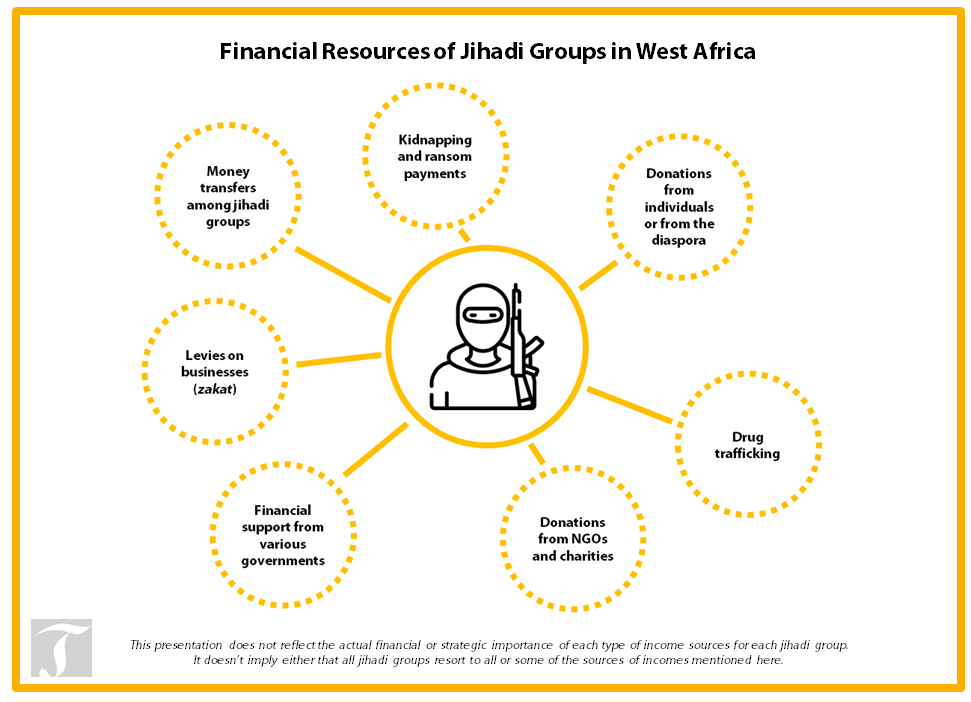

Despite the joint efforts of the international community, Jihadi groups operating in West Africa have maintained their actions and have even expanded, resorting opportunistically and with great pragmatism to various funding sources. It is of course difficult to provide quantitative data on each of these sources and to track them precisely. Nevertheless, three typical features of these funding mechanisms can be identified. First of all, groups that are localized on a specific area get funded locally. Second, most operations undertaken by these groups are cost effective. Finally, jihadi groups rely on religion, local conflicts, anti-western rhetoric, corruption of government officials and the general feeling of injustice to gather support. In that regard, if strengthening anti-terror financing procedures remains a priority, it is necessary to acknowledge that money is just one trigger among many others.

On March 28th 2019, the UN Security Council voted for resolution 2462 to fight terror financing. The resolution was drafted in the wake of the IS terror group’s collapse in the Middle East. It is particularly meant at implementing the Paris Agenda, adopted in April 2018 during the “No money for terror” international conference organized in the French capital. Although that resolution was a significant milestone in setting a resolute intensification of the international community’s efforts, anti-terror-financing policies had already been developing for several decades. The turning point took place in the 1990’s and 2000’s as anti-terror-financing became a pillar of international strategies targeting terror groups. The point was to exhaust their financial resources by targeting the individuals and organizations sponsoring them.

West Africa was also impacted by these developments. In 2002 and 2003, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) adopted regulation n°14/2002/CM/ UEMOA and decision n°06/2003/CM/UEMOA relevant to the freezing of funds and other financial resources. These were adopted as part of a set of anti-terror financing policies. They were followed in 2007 by directive n°04/2007/CM/UEMOA also relevant to Counter Financing of Terrorism (CFT) procedures (the latter was replaced in 2015 by directive n°02/2015/CM/UEMOA relevant to anti-money laundering (AML) and CFT within

the member states of the UEMOA). Additionally, the Intergovernmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA) published typology reports on this topic (1). Nevertheless, despite these efforts, reality on the ground is rather grim: jihadi groups operating in the Sahel region and the areas surrounding Lake Chad have maintained their activities and even expanded. While the international community is intensifying its joint CFT efforts, the current resilience of jihadi groups leads to question the resources they have access to, as well as their needs. This also leads to question the role played by money in their development. By extension, this amounts to questioning whether and how these groups are vulnerable to strategies focused on stifling their financial resources. Finally, we need to assess the types of challenges faced by countries in West Africa when it comes to CFT implementation (2).

“Narco-jihadism” as a Myth

Contraband in drug and narcotics, especially in cocaine and cannabis resin, more recently tramadol (3), has been commonly considered for years – and still today (4) – as a key financial resource for jihadi groups operating in the Sahel region. Some go even as far as stating that jihadi groups would be major players in this trafficking. The popular concept of “narco-jihadism” was widely used in the 2000’s, as many saw a strong link with the criminal aspects of the civil war in Algeria. Nevertheless, this analysis doesn’t convey the reality of relations between jihadism and narcotics trafficking.

Several reports have mentioned that drug trafficking convoys were paying levies to jihadi groups to be authorized to circulate on their territories. At some point, some reports even mention jihadi groups providing security escort services on short distances (5). The Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MOJWA) was also in touch with infamous drug dealers from Arab origin, members of the Lamhar tribes in the region of Gao, in Mali (6). Since France’s Serval military operation (January 2013) and subsequently to an increased military pressure, Jihadi groups would even show some levels of tolerance towards drug dealers and their contraband activities (7).

|

Performative Speeches • Although organized crime breeds instability and impacts peace making processes, and jihadi groups have relied on trafficking to expand their support base, both to reach operational and logistical objectives, violence in the Sahel region is not solely to be explained using economic considerations. AQIM’s development in the Northern Mali and the collapse of the Malian government in 2012 are not primarily linked to trafficking and organized crime. Similarly, simplifying drug trafficking as an extension of terrorism or the conflicts in the North of Mali as a mere result of crime related trends conveys a misleading representation of the situation. Such simplifications lead to denying any reality to the jihadi’s projects while still avoiding questioning about the reasons why individuals resort to such actions. Doing so prevents from addressing the dynamics of social grievances, political violence, the role of religious references as well as the logic behind the tolerance towards drug trafficking by jihadi groups. Moreover, these speeches elude the political implications triggering the rebellion in the North of Mali, as the coup of 2012. They also elude the responsibility of authorities in the ensuing government crisis. Ultimately, such considerations shy away from looking at the main players involved in the deterioration of the situation as well as from the many political ramifications of drug-trafficking (8). This was illustrated by the case of a few government officials from Mali involved in the landing of a Boeing aircraft carrying 11 tons of cocaine, in Tarkint (Gao region) in November 2009 (9). |

According to a report published by the UN in January 2019, fighters from the Al Mourabitoune group have been involved in narcotics trafficking. It is impossible at this stage to quantify their participation due to an obvious lack of data (10).

This being said, a report published by the International Crisis Group on narcotics trafficking in Mali, reminds that the thesis, according to which leaders of jihadi groups have been involved directly in drug trafficking, is not substantiated (11). It is also necessary to establish distinctions between the groups and their individual members, as well as between the orientations provided by their leadership, the way local cells are being controlled and the fighters themselves (who in certain cases enjoy some level of autonomy). Generally speaking, it is important to take into account how each of the Al Qaeda or IS affiliates chose to interact with narcotics trafficking (12). The case of Gao in 2012 is in that regard highly interesting. On the one hand, close relations between jihadis and drug dealers have generated strong debates within the MOJWA. On the other hand, in the region of Kidal, narcotics traffickers were requested to put an end to their business. In Timbuktu, Abu Zeid expelled the local Berabish militia involved in drug trafficking activities.

The links between jihadis and narco-traffickers goes beyond questioning their involvement in the narcotics business, it is also relevant to two other dimensions. First, it is relevant to the control over the region’s territories and their inhabitants. Jihadi groups operating in the North of Mali have indeed been able, despite France’s 2013 military intervention, to levy money on trafficking operations and the relevant side revenues. Members of Ansar Eddine or of the MOJWA have joined groups that were signatories of the 2015 Peace and Reconciliation Agreement in Mali. Local tribes, from where fighters of the Group to Support Islam and Muslims (GSIM) (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam Wal Muslimin, JNIM) collect levies from convoy transiting through their area of influence, similarly to Ansar Eddine in the region where they are located. Sellers can also be solicited to finance war operations when needed. This was reminded by Abu Al Hassan Al Rashid (13), the Chief “Islamic Judge” of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), in a letter dated from October 2011 sent to Boko Haram fighters (14). Among others, he was mentioning that collecting levies from rich individuals was a legitimate way to finance jihad and its fighters.

Then, beyond the question of financing and the relevant practices, it is important to remember that jihadis and criminals, whether involved or not in the drug trafficking, live on the same territory, may belong to the same ethnic group the same tribe or even the same family. The latter strengthens feelings of cohesion and solidarity. It can further lead to some regrouping according to opportunistic and pragmatic goals without necessarily indicating any moral support for a given cause. As a matter of fact, there is no clear segmentation between these two worlds. This can easily be seen in the case of hostage taking situations or in the ensuing negotiations to release the captives. Traffickers have also been involved in attacks, while others did join jihadi groups such as Sultan Ould Baly in Mali, or Bana Faye in the Lake Chad region. More generally, fighters do carry with them knowledge and experience from their previous commitments, in addition sometimes to some useful relations, if not even stakes in the ongoing trafficking. The latter reinforces the links between jihadism and crime (15). In a report published in August 2019, members of the Group of Experts created to implement resolution 2374 (2017) of the UN Security Council, were stating that a drug trafficker would have provide financial support to a jihadi group. The report also mentions a bribery attempt aiming at freeing individuals condemned for charges of terrorism (16).

Multiple Financing Sources

More than drug money, other sources of financing have played a key role in embedding jihadi groups in the Sahel region, with kidnapping and ransoming topping the list. Between February 22nd and March 23rd 2003, Abderrazak El Para, a top executive of the Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC), kidnapped 32 European tourists in the South of Algeria. Between 2008 and 2013, several kidnappings have been claimed by AQIM, most hostages being released after negotiations. This multiplication of kidnapping operations was followed by an inflation of the sums demanded to secure the liberation of hostages, ranging from a few hundred thousand to several million euros per hostage (17). Ransom demands or alternatively the liberation of jihadi prisoners have been perpetuated: a ransom of 10 million euros was allegedly demanded to free Swedish and South-African hostages captured in Timbuktu on November 25th, 2011. Whether or not the requested amount was delivered has not been confirmed (18). Several cases of kidnaping and ransoming of local hostages were also accounted for. In the region of Diffa, for instance, ransoms were payed by families to free their relatives. According to local sources, several of these kidnappings were performed or were ordered by fighters from jihadi groups located in the Lake Chad region (19). Similarly, in Central Mali, several government representatives were kidnapped (this involved public figures such as judges, security officers, governors, civil servants, etc…) and the payment of ransoms was also reported in some cases, such as the one of Amadou Ndjoum, who had been captured in April 2017 and released five months later (20).

More broadly, Jihadi groups collect money and goods on economic activities. They can collect it from the trafficking of licit goods, such as gas or cigarettes in Mali, those two being strong income sources for criminal gangs and armed groups that are signatories of the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Mali (2015) (21). They collect it also from fishing and cattle businesses in the Lake Chad region (22). In Central Mali, in 2017, katibas operating in the north of the Mopti area organized the greatest part of herds’ migration for a lesser cost than what herdsmen usually pay to government representatives and local chiefs (dioros), managing grazing lands in the Fulani society (23). Cattle is stolen and then given to jihadi groups, who resell them to finance their fight, while getting embedded in local conflicts. This method has allegedly been widely used by the group Ansarul Islam. The latter allegedly benefited greatly from the reselling of animals captured in Mali (24). The gold industry is a specific area of concern for many (25), be it concerning the ransoming of companies, levies on the benefits of miners or the site managers in exchange for safety and at times, in the reselling of the collected ore.

Finally, jihadi groups enjoy external financial support, the latter is very difficult to quantify but is definitely tangible and relevant to various categories. Some of these incomes, most likely the majority of them, are provided by private individuals. New recruits transfer their goods to the group upon enrolment. In 2017, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the katiba of Macina allegedly received financial support (as donations) from herdsmen and local businesspeople (26), some of them actually members of the Fulani diaspora established in Saudi Arabia (27). Several testimonies mention also levies and taxes collected from herdsmen in Central Mali – more or less amounting to a zakat payment, an Islamic tax – in an area located at the border between Mali and Niger. Reports also account for similar situations in the Lake Chad region (28). In October 2018, the mayor of Inates (Niger, Tillabery region) was protesting against the payment of “taxes” to jihadi groups by some of his constituents (29).

“Investments” across various groups constitute a second category. In 2010, Abubakar Shekau thanked Abu Zeid, who was then one of AQIM’s top executives in the Sahara, for providing training and for his “financial generosity” (30). Transfers survived the occupation of the North of Mali in 2012 (31). Though on a different scale, the IS in Iraq and Levant (ISIL) could finance its own branch in the Sahel and the Lake Chad regions (32). While organization members allegedly had “hidden great amounts of cash in [their] main areas of operations and had transferred some of it secretively to neighboring countries” (33), ISIL’s publications in the first semester of 2019 seemed to convey a strengthening of their ties with ISGS – ISIL indeed published images of operations in the Sahel region. Similarly, ISIL seemed to be willing to emphasize the role of ISGS’s leader, Adnane Walid Al Sahraoui (34).

Donations by NGOs or charities do constitute a third category. Several investigations have been launched on suspicion of terror financing by not-for-profit organizations (35). The current situation is reminiscent of the 1994 closure of several NGOs in Mauritania, after they were accused of terror financing (36). Nevertheless, most transfers are relevant to private individuals and would come from sympathizers. Some of the funds are transferred via official financial vehicles – via charities, religious foundations or the financing of mosques. Otherwise, money transfers are also organized via informal networks of shopkeepers (37).

The last category worth mentioning, although it must be considered very cautiously, is that of government funding. In August 2019, a newspaper from Mali stated that over 300 million XOF (approx. 455 000 euros) were allegedly transferred to executives in central Mali, and that some part of the amount landed in the hands of Koufa’s fighters (38). This has not been confirmed yet. Nevertheless, as was reminded in a report published by the French Assemblée Nationale on terror-financing, government funding does not constitute in itself a direct sponsor of terrorist group. But it involves rather other strategies, which can indirectly result in the financing of terror groups (39).

This short summary of the diversity of financing resources leads to three main conclusions. First of all, if some sources of income require a centralized management (such as hostage taking operations or the transfer of funds by some groups to a well-known leader), others can be organized more autonomously by local entities. Second, terror financing can be seen as a mix of financial, political and social considerations. Kidnapping Western hostages or government officials, stealing cattle from rich merchants, considered also as cooperating with Islam’s enemies, are all very effective ways of collecting money for terrorist groups. Such operations serve also a larger purpose. As a matter of fact, they can be used as tools of propaganda and power, and contribute to strengthening the terror group’s grip on the local population if not, for some circles, its popularity. It can also be perceived by business owners and herdsmen as a protection worth paying to ensure the viability of their activities. Finally, funding resources tend to change shapes and scales at various levels, which interact with one another in a great variety of contexts – ranging from local levels to national, regional and global perspectives. What matters above all is the interaction happening at the local level and how it is impacting the relevant territory.

Money, a Trigger for Violence Among Many Others

If there is a great variety of sources of funding, organizing and leading terror operations doesn’t require a lot of means. Great amounts of weapons and ammunitions are acquired following raids on key targets. Access to components of improvised explosive device (IED), except landmines, is easy and rather cheap. The same statement can be led for attacks performed outside of the main control territory of terror groups. The organizers of the 2016 Ouagadougou attack mentioned a budget of 10 million XOF (approx. 15 000 euros) (40) to identify potential targets (transportation, accommodation, fake documents acquisition (41), return tickets), the planning of the operation (rental of an accommodation space (42), supply of weapons and material, including a potential modified version of the vehicle(s) used in the attack, logistics and transportation of fighters, target identification by the terrorist commando), the release of the terrorist commando on the site, and then the return of the support team. The mentioned amount of money includes the remuneration of the organizer. The latter shows that organizing attacks can be a profitable business per se. In comparison, the amounts spent for the attacks in Bamako are even smaller, topping a maximum of a few thousand euros. Nevertheless, these estimates must be considered with great caution. Everything is not necessarily bought or bartered: in addition to the vehicles repatriated from other attacks, others are stolen before being used in operations. These estimates still give a general idea of the limited costs involved in perpetrating terror attacks.

Focusing solely on the costs inherent to the organization of attacks doesn’t fully reflect the financial needs of a terror group. There are indeed two types of expenses: those that are used for operational purposes (including the training of fighters, the planning and the execution of attacks) and those that are used for organizational purposes (the spreading of the organization’s ideas and visions, communication cost, the training of new fighters as well as costs relevant to ensuring its safety and protection) (43).

Money is a leverage used to recruit and operate a network of suppliers and informers. It is also used to attract new recruits, sub-contract some activities and purchase favours. Sources mention amounts ranging from 50 to 150 euros to set an IED, to which bonuses are sometimes additionally offered if the operation resulted in the death of members of international forces (44). Similarly, the two Malian fishermen who were arrested with Fawaz Ould Ahmed – held responsible for the 2015 attack on Bamako’s La Terrasse – have mentioned the instrumental role played by money in their recruitment. The first one, who had been approached at a wedding party, told investigators that he had asked “whether he could make money with this opportunity”. As he had been answered positively, he had also noted with great satisfaction that his leader “could afford beef and mutton” for the meals served at the training camp. The second fisherman stated he had joined Al-Mourabitoune “because he was the only young guy remaining in his village”. He also added that he had been promised some money: “we followed them for the money that was promised to us by the recruiters” (45). Of course, claiming financial needs can be a defence strategy when facing prosecution. Nevertheless, these two testimonies bring to attention the use of money to attract and impress new recruits. It also brings to light the low-cost aspect of recruitment. The first one mentioned an amount 190 euros in cash as “pocket money” before going back to his village. The second one mentioned the grant of a small motorbike and of approximately 400 euros, of which a little over 300 euros were supposed to be used for his wedding (46).

Joining a terror group is not just about the money. Fawaz Ould Ahmed’s and Bechir Sinoun’s careers in terror organizations were not motivated by the necessity to address financial needs but rather by a gradual process of radicalization. Bechir Sinoun was the Tunisian attacker responsible for the assault on the French Embassy in Mali on January 5th, 2011. Such individuals turned to terror to address personal issues of existential nature, general feelings of anger and out of support for the Islamist cause (47). More generally, recent research on the motivations for joining Jihadi groups in Mali demonstrated the strong incentives generated by a general feeling of injustice and a yearning for protection. On the one hand, crimes committed by defence and security forces and more generally the behaviour of state representatives (48) play a great part in the delegitimization process of the State as an authority and in pushing some individuals to join armed rebellions (49). On the other hand, if Jihadi groups are willing to impose a new moral order of their own, they also exert brutal and pitiless violence against their opponents, government officials or civil society leaders disputing their ideas, in order to scare them away or simply eliminate them… all while finding astute rationales to legitimize the use of violence (50). One of the consequences of such commitments is to involve an even larger set of individuals in order to protect their families, their possessions, their lives as they try to put up with the new situation.

If money is only one trigger for violence, among many others, and if the cost of operations remains rather limited, it is nevertheless important to not to dismiss its significance. It acts primarily as a multiplier of force. Lacking money impacts negatively the groups’ operational capacity. That was the case of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) in the Philippines. Documents that were uncovered in 2006 following a military operation demonstrate that JI planned to set up a chemical weapon production facility and to launch massive attacks in Manila. They nevertheless were unable to reach their objectives as they were not sufficiently funded for that type of operations (51). Then, in the long timeline of global jihad, money enables it to settle in a territory, extend its network by relying financially on sympathizers, and structure the fight – namely by encouraging sympathizers to take action – disseminate the ideology and establish oneself as an authority. “Osama Bin Laden’s major asset had been his immense wealth, Lemine Ould M. Salem recalls. It enabled him to confirm and then extend his authority and that of his organization […]. It is true that modern jihadism was partly favoured by a series of political factors […]. But it also encompasses a highly economic and material component” (52).

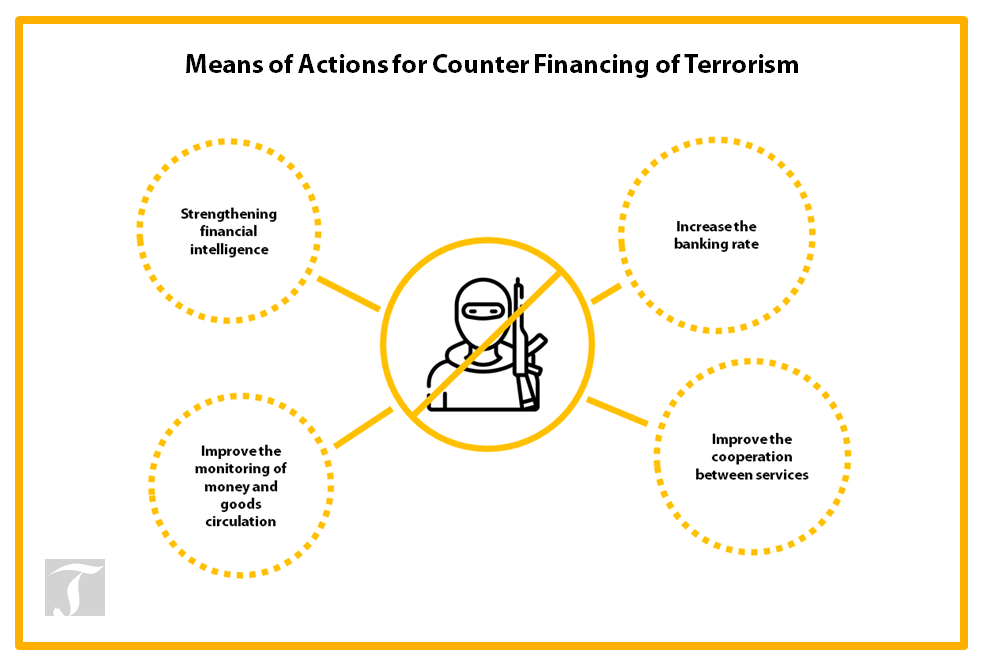

A Need to Strengthen CTF Procedures

The January 29th 2018 meeting report of the AML Liaison Committee of the Franc Area describes extensively some of the challenges that governments in West Africa need to face to implement counter terrorism financing (CTF) effectively. First of all, from a legislative perspective, the July 2015 directive issued by the West African Economic and Monetary Union had been transferred in just four countries (Mali, Niger, Ivory Coast, and Burkina Faso). In the four remaining countries (Benin, Senegal, Togo and Guinea-Bissau), the process was still ongoing. During this meeting, representatives of the GIABA had also stressed that additional measures would have to be taken to cover aspects left unaddressed by the 2015 directive in consideration of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) (53). Also, the number of convictions relevant to money laundering and terror financing – both topics being mentioned jointly in the meeting report – has remained very limited: one in 2014 (Senegal); three in 2015 (Ivory Coast and Senegal); none in 2016; three in 2017 (Mali, Niger and Senegal) (54). Insufficient funding, lack of human resources, defective communication with constituents and a limited integration with other services were mentioned as the main problems faced by financial intelligence units (55).

These findings question the impact of excessive red tape, the absence of effective cooperation and potentially the lack of sincerity when considering the level of priority given to anti money laundering (AML) and CTF. Three main sets of measure must be prioritized, among all the means of action mentioned in the UN resolution 2462 of March 28th, 2019.

The first one had already been mentioned, i.e. the reinforcing of financial intelligence units and their relations with other relevant stakeholders – be they government related or not –, starting with investigators in charge of terror related files. The point is to enable a better consideration of the financial aspects of terrorism in investigations. Another specific item is about the centralization and capitalization of knowledge in financial intelligence units. Second, far from being unique to a few structures, the CFT requests the mobilization of a set of administrations, and doing so, ensuring effective cooperation among the various stakeholders. The military, intelligence agencies, customs, the police and the judiciary have all a role to play along representatives of the financial system in order to improve knowledge and practices. The point is to be able mobilize the relevant tools and procedures as various situations demand it. Similarly, as reminded in the Paris Agenda (April 2018), an effective international cooperation (in terms of information sharing, common mobilization and support) is a must. Thirdly, as in West Africa the banking rate is between only 5 to 15%, and as jihadi groups make use of the informal nature of local financing systems, fighting for more financial transparency remains a top challenge. This leads to the deployment of measures to increase the banking rate, but also to a more effective monitoring of cash circulation, informal money transfers and of the circulation of goods and merchandise.

It is in fact unrealistic to expect that CFT measures will cut out funding of terrorist groups in West Africa. Neither will that prevent them from perpetrating attacks. The reasons are multiple, starting with the amount of money generated by trafficking in addition to the practices of local administrations and the private sector, to aspects of local financial and tax cultures. All of these can lead to a strong resistance against more transparency, with in the background specific triggers for violence and the generation of revenues inherent to the control of territories and their populations (56). Nevertheless, efforts in counter financing in terrorism can contribute to better manage national economies and encourage state building processes, and play a major role in finetuning our knowledge and understanding of financing resources of jihadist groups. Doing so would contribute to better address the challenges set by the financial networks used by the supporters of the jihad to spread their ideology.

Notes •

(1) See GIABA, Financement du terrorisme en Afrique de l’ouest, October 2013, available here and Terrorist Financing in the West and Central Africa, October2016.

(2) The author addresses his thanks to Amandine Gnanguenon and Bérangère Rouppert for proofreading this text and providing precious insights. Potential erroneous facts or analysis are the sole responsibility of the author.

(3) Similar discussions were held, especially in Nigeria, regarding Tramadol trafficking. If some reports did mention that some Boko Haram fighters might have used this drug, most trafficking flows transiting through Nigeria do not pass through the region of Maiduguri (interviews, Niamey and Abuja, 2018 and 2019).

(4) Observations of the author.

(5) See for instance Djallil Lounas, “The Links Between Jihadi Organizations and Illegal Trafficking in the Sahel”, MENARA Working Papers, November 2018. AQIM would have justify, in a 2013 October statement, accepting drug trafficking money by explaining that drug targets Europe and is in itself a weapon against the West.

(6) Wolfram Lacher, “Le mythe narcoterroriste au Sahel”, the referring document used by the West African Commission on the Impact for Drug Trafficking on Governance, Security and Development in West Africa (WACD), n°4, 2013; Mathieu Pellerin, “Narcoterrorism: Beyond the Myth”, in Cristina Barrios et Tobias Koepf (dir.), Re-mapping the Sahel: transnational security challenges and international responses, EU Institute for Security Studies, Report n°19, June 2014, pp. 25-31; Francesco Strazzari, “Azawad and the Rights of Passage: The Role of Illicit Trafficking in the Logic of Armed Group Formation in Northern Mali”, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Center, January 2015.

(7) International Crisis Group, Narcotrafic, violence et politique au Nord du Mali, Africa Report n°267, 13 December 2018, p. 14.

(8) Wolfram Lacher, art. cit.

(9) Laurent Guillaume, “Le trafic de stupéfiants en Afrique, une menace en perpétuelle évolution”, in Laurent Guillaume (dir.), Africa Connection, Paris, La manufacture de livres, 2019, pp. 13-56 et 28.

(10) Nations Unies, Twenty-third report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, New York, S/2019/50, 15 janvier 2019, p. 12.

(11) See Wolfram Lacher, art. cit., Djallil Lounas, “The links between jihadi organizations and illegal trafficking in the Sahel”, op. cit., and International Crisis Group, op. cit.

(12) International Crisis Group, op. cit.

(13) That leader of AQMI was killed in December 2015 during an ambush in the Tizi Ouzou region (Algeria).

(14) Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “AQMI Advice to ‘Boko Haram’ Dissidents: Full Translation and Analysis”, 15 September 2018.

(15) International Crisis Group, op. cit.

(16) United Nations, Final Report of the Panel of Experts Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2374 (2017) on Mali and Renewed by Resolution 2432 (2018), S/2019/636, 7 August 2019, pp. 32-33.

(17) In order to compare the costs mentioned in the media between 2003 and 2013, see for instance: “Otages du Sahara : force rançon”, Libération, 22 August 2003 et Célian Macé, “ »Otages d’État » : rançons et soupçons au Sahel”, Libération, 26 January 2017.

(18) Press conference organized by Gift of the Givers, a South African NGO, following the release of Stephen McGown, August 2017.

(19) Interviews, Niamey, March 2018.

(20) “Oumar Cissé : « L’enlèvement d’Amadou Ndjoum avait pour seule motivation l’argent”, Bamada.net, 21 September 2017.

(21) United Nations, Mid-Term Report of the Panel of Experts on Mali, S/2019/137, 21 February 2019, p. 2.

(22) Malik Samuel, “Economics of terrorism in Lake Chad Basin“, ISS Dakar, 10 July 2019.

(23) United Nations, Final Report of the Panel of Experts Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2374 (2017) on Mali, S/2018/581, 9 August 2018.

(24) Interviews, Abidjan, February 2019.

(25) United Nations, Final Report of the Panel of Experts Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2374 (2017) on Mali and renewed by Resolution 2432 (2018), op. cit., pp. 47-48.

(26) Interviews, Bamako, September 2017, and Niamey, March 2018. These donations are not necessarily ideologically motivated. They may be intended (as in Gao in 2012) to pursue commercial activity and to benefit from protection.

(27) International Crisis Group, Mali central. La fabrique d’une insurrection ?, Africa Report n°238, 6 July 2016, p. 12. In this context, both the ethnicization of conflicts, with groups asserting their Fulani identity, the denunciations of corruption of Sahelian elites and the West are vectors of mobilization alongside references to religion.

(28) See FIDH et AMDH, Dans le centre du Mali, les populations prises au piège du terrorisme et du contre-terrorisme, report n°727, November 2018, p. 36, International Crisis Group, Frontière Niger-Mali: mettre l’outil militaire au service d’une approche politique, Africa Report n°261, 12 June 2018, p. 12 and International Crisis Group, Facing the Challenge of the Islamic State in West Africa Province, Africa Report n°273, 16 May 2019.

(29) M.H., “Le maire d’Inatès se réfugie à Tillabéry”, L’Enquêteur, October 2018.

(30) Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram’s al-Qaeda Affiliation: A Response to « Five Myths about Boko Haram“, Lawfare Institute, 1st February 2018. Note that Jacob Zenn’s considerations were answered in the following paper: Adam Higazi et al., “A Response to Jacob Zenn on Boko Haram and al-Qa‘ida”, Perspective on Terrorism, Vol. 12, N°2, April 2018, pp. 203-213.

(31) Interview, Niamey, February 2016. Financial flows are not one way. In 2015, Abubakar Shekau donated 15,000 euros to Senegalese leaving the Sambissa Forest in Nigeria. If no instructions are given, it is likely that the purpose is to extend jihad.

(32) According to a report published recently (The Global Initiative for Civil Stabilisation, Survival and Expansion, the Islamic State’s West African Province, April 2019), ISIL allegedly financed its branch in the Lake Chad region. According to the author, most of the funds, though, were collected locally.

(33) United Nations, Eighth Report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the United Nations efforts to assist Member States in countering this threat, S/2019/103, 1st February 2019, p. 3.

(34) In his April 29th 2019 interview, broadcasted by Al Furqan, Al-Bahgdadi explicitly refers to the leader of IS in in the Greater Sahara region.

(35) FATF-GIABA-GABAC, Terrorist Financing in West and Central Africa, op. cit., pp. 14-15.

(36) Interview, Nouakchott, October 2016.

(37) Marc Mémier, AQMI et Al-Mourabitoun : le jihad sahélien réunifié ?, IFRI, January 2017, p. 34.

(38) “Mali: les dessous de la visite de Boubou Cissé dans le centre”, Nord Sud Journal, 5 August 2019.

(39) Valérie Boyer et Sonia Krimi (rap.), Rapport d’information sur la lutte contre le financement du terrorisme international, Commission des Affaires étrangères de l’Assemblée nationale, 3 April 2019, p. 30.

(40) Morgane Le Cam, “Burkina Faso : le principal commanditaire de l’attentat de Ouagadougou identifié”, Le Monde, 24 March 2017.

(41) According to a former jihadist, a false document cost a few years ago 15 000 XOF, less than 25 euros, (Élise Vincent, “Les confidences d’ »Ibrahim 10″, djihadiste au Sahel”, Le Monde, 25 February 2019).

(42) Example among others, the members of the cell dismantled in Ouagadougou in May 2018 had paid 120 000 XOF (less than 200 euros) in cash for three months of rent, through a third person.

(43) Jean-Charles Brisard, Terrorism Financing. Roots and Trends of Saudi Terrorism Financing, Report prepared for the UN Security Council, December 19th 2002, p. 7.

(44) Nathalie Guibert et Morgane Le Cam, “ »C’est l’arme des lâches » : au Mali, l’opération « Barkhane » face aux mines artisanales”, Le Monde, 22 May 2019. The use of paid intermediaries has also been documented in relation to hostage taking or assassination.

(45) Quoted by Élise Vincent, “Les confidences d’ »Ibrahim 10″, djihadiste au Sahel”, art. cit.

(46) Ibid. This absence of paid salary can be found in the katiba of Macina, which doesn’t prevent the group from providing other forms of remuneration. Former fighters have thus stated that “they hadn’t received any salary. Nevertheless they had access to stocks of food, were able to protect their cattle and that of their relatives, they were also offered the opportunity to make money by escorting pastors who requested protection” (Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni et al., “Jeunes « djihadistes » au Mali. Guidés par la foi ou par les circonstances ?”, Analytical Note n°89, ISS Dakar, August 2016, p. 7.

(47) Ibid. and Matthieu Suc, “Les confessions du « stagiaire » d’Al-Qaïda”, Mediapart.fr, 24 May 2017.

(48) See for instance Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni et al., art. cit., and Mathieu Pellerin, Les trajectoires de radicalisation religieuse au Sahel, IFRI et OCP, February 2017.

(49) See for instance: UNDP, Journey to Extremism in Africa, New York, 2017. For more documentation on some abuses perpetrated in 2018 and how they were instrumentalized by Jihadi groups: Morgane Le Cam, “Au nord du Burkina Faso, les exactions de l’armée contrarient la lutte antiterroriste”, Le Monde, 12 May 2018.

(50) For Central Mali, see for instance: FIDH and AMDH, op. cit., pp. 36-40. An example of “stick and carrot” situation is the assassination of the commander of the Mécanisme opérationnel de coordination (MOC) in Timbuktu in September 2018, especially in consideration of the letter left to explain the execution. The author, addressing the Oulad Driss, mentions three main topics legitimating the killing: Islam gathers the Oulad Driss and the Group to Support Islam and the Muslims; M’Begui had become an apostate because he had joined the MOC and his killing is nothing less but the implementation of God’s justice; M’Begui had been warned several times against the risks of joining the MOC and was aware of what would expect him; Yahia Abou al-Hammmam, who signed the letter, offers to organize a meeting with the Oulad Driss to address potential grievances and sources of dissatisfaction of the tribe (Alex Thurston, “Mali: An AQIM/JNIM Assassination in Timbuktu and Its Aftermath”, Sahel blog, 24 September 2018).

(51) Arabinda Acharya, Targeting Terrorist Financing. International Cooperation and New Regimes, Oxon, Routledge, 2009, p. 2.

(52) Lemine Ould M. Salem, L’histoire secrète du Djihad. D’Al-Qaida à l’État islamique, Paris, Flammarion, 2018, p. 223.

(53) AML liaison committee of the Franc Area, “Compte-rendu de la réunion du CLAB du 29 janvier 2018 et synthèse des interventions”, pp. 4-5. Except in Togo, where the project was still being considered by the government, the draft bill had been adopted by the Ministerial Councils and forward for adoption to the national parliaments of the three other countries.

(54) Ibid., p. 5.

(55) AML liaison committee of the Franc Area, Rapport annuel du CLAB 2016, pp. 4-5.

(56) This finding is not unique to West Africa. For a critical overview of research methodologies and of their expected results, see Peter R. Neumann, “Don’t Follow the Money. The Problem with the War on Terrorist Financing”, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 96, n°4, July-August 2017, pp. 93-102.